Western analysis exploring the implications of the Taliban’s August 2021 takeover for Beijing has often centered upon its significance for the Belt and Road Initiative, mineral extraction efforts, and America’s commitment to its allies. Western analysts seeking to understand the significance of Kabul’s fall for China should also take into account the following underrecognized dynamics that are likely to inform Beijing’s response.

High-Tech Vs. Low-Tech Combat

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) – at odds with prevailing Western narratives of China’s technological sophistication – exhibits a surprising level of comfort with low-tech warfare.1 The PLA’s low-tech capabilities were apparent, for example, in the June 2020 China-India border clash in the Galwan Valley in eastern Ladakh. Fighting did not involve firearms or explosives – whose usage a 1996 agreement prohibited along the border – but stones and wooden sticks wrapped with barbed wire.2 The Taliban’s victory over the better-equipped Afghan National Army may reaffirm to Beijing the importance of low-tech warfare, especially against U.S.-aligned forces.

Continental Warfare

The centrality of territorial control to the Taliban’s success in Afghanistan may reinforce to Beijing the continued importance of land-based warfare, especially as Western elites increasingly conceive of military power in terms of technology.3 In recent years, China’s leadership has been clear about the importance of territorial control: for example, in a 2018 meeting with then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis, President Xi Jinping asserted that “we cannot lose even one inch of the territory left behind by our ancestors.”4 Practically, PLA forces have taken territory on China’s borders with India and Bhutan; even in the South China Sea, China’s artificial islands represent echoes of land-based warfare.

The sign marking the turnoff from G314 (southbound to Khunjerab Pass) to Kalaqigu, the gateway to the China-Afghanistan border.

Morale and National Unity

President Xi has emphasized cultivating a stronger national spirit, suggesting that he considers it an area of weakness for China.5 Reports that a lack of morale may have contributed to the Afghan National Army’s rapid defeat could heighten Beijing’s urgency to develop greater national morale.6 Conversely, reports of the Taliban’s strong moral confidence may heighten Beijing’s pessimism about its ability to assimilate non-Han ethnic populations, especially Uyghurs, and reinforce a widespread belief that they are inherently non-Chinese and, in some sense, unchangeable.7

Illicit Drugs

President Xi has placed particular emphasis on eradicating drug usage in China, explicitly linking the issue to national security and advocating extreme policies to seek out and punish drug users.8 This focus could affect China’s decision-making related to Afghanistan: the Golden Crescent – comprising Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran – is one of the three major providers to the Chinese drug market.9 Although China has had success in reducing drug entry from the region over the past decade, concern for a potential resurgence appears well-founded. In 2020, the Golden Crescent’s heroin penetration into China increased, in line with the Ministry of Public Security’s 2019 assessment that China – even prior to the most recent instability along the border – remains “at risk to the infilitration of drugs” from the region.10

A view of the valley that leads from Tashkurgan to the China-Afghanistan border. Behind the mountains to the left lies Pakistan; behind the mountains to the right lies Tajikistan. This valley has long been inaccessible to visitors.

The Uyghurization of Xinjiang’s Tajiks

For well over a century, firewalls and divisions between regional populations within Xinjiang have prevented a unified force from challenging Chinese power.11 China has continued to apply this strategy: to ensure Tajiks on both sides of the China-Afghanistan border remain separated, for example, Chinese authorities rarely issue Tajiks passports, thereby impeding potential travel to Afghanistan.12 Yet in recent decades, Beijing’s rule over Xinjiang has been complicated by the increasing homogenization of non-Han cultures in Xinjiang, including the Uyghurization of ethnic Tajiks who are China’s closest populations to its border with Afghanistan.13 The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan risks emboldening China’s ethnic Tajiks, and tellingly, Beijing has raised concerns about increased cross-border exchanges.14

Karasu Port, the official checkpoint on the Chinese side of the China- Tajikistan border crossing. Until 2004, there was no official border crossing between China and Tajikistan, reflecting the sensitivity of the border due to its proximity to Afghanistan.

Xinjiang’s Kunlun Foothills

The mountainous area stretching eastward from the China-Afghanistan border is one of the most consequential thousand square miles of Chinese territory. Yet its location near China’s borders with Afghanistan and Pakistan for years has made this region effectively off-limits to non-locals. Towns such as Sanju – itself more than 100 miles away from China’s formal borders – have been far more closed off than the rest of Xinjiang, with checkpoints making legal access impossible for most travelers, and far less penetration of Mandarin knowledge than other parts of southern Xinjiang. Tellingly, although Uyghur attacks reported in the media mainly occurred in urban and oasis areas of the province, individuals in southern Xinjiang have conveyed rumors of larger, more sophisticated attacks in the Kunlun foothills; it is perhaps no coincidence that security forces in this region have appeared far more sophisticated than elsewhere in Xinjiang.15

A police stop in Sanju, an oasis town in Xinjiang that historically served as a gateway into the Kunlun mountains for international trade.

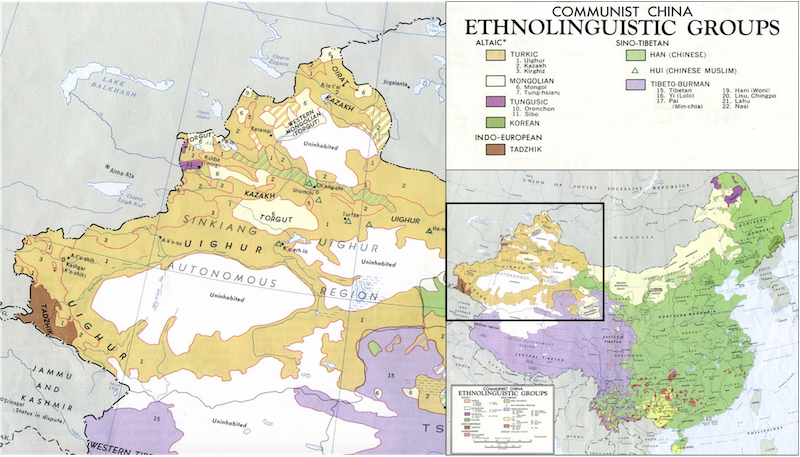

The above map depicts the location of Tajiks along the China-Afghan border, along with the complex geographical distribution of Uyghur and Kyrgyz populations. Although over 50 years old, this remains one of the clearest maps of China’s ethnolinguistic groups. Note: the indication of a Kazakh population in the Kunlun mountains may be an error. Source: “China – Ethnolinguistic Groups from People’s Republic of China Map,” U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Directorate of Intelligence, Office of Basic Geographic Intelligence, 1967, accessed via Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:China_ethnolinguistic_1967.jpg.

Endnotes

1 Historical context illuminates China’s interest in this style of warfare: due to a lack of internal trust, Chinese leadership preferred poorly armed soldiers over well-equipped ones to prevent the contingency of an armed uprising. See: Clarence D. Bruce, In the Footsteps of Marco Polo, Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1907, 292.

2 “China Suffered 43 Casualties in Violent Face-off in Galwan Valley, Reveal Indian Intercepts,” Times of India, June 16, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/china-suffered-43-casualties-in-violent-face-off-ingalwan- valley-reveal-indian-intercepts/articleshow/76411372.cms.

3 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley, for example, has noted that “the country that masters … [emerging] technologies … is likely to have a significant and perhaps decisive advantage [in war].” See: David Vergun, “Milley Discusses What It Takes to Remain World’s Preeminent Fighting Force,” U.S. Department of Defense, August 2, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2716534/ milley-discusses-what-it-takes-to-remain-worlds-preeminent-fighting-force.

4 See: “Xi Tells Mattis China Won’t Give Up ‘One Inch’ of Territory,” CGTN, June 28, 2018, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d514d3545444e78457a6333566d54/share_p.html.

5 See, for example: “Be More Patriotic, China’s Xi Tells Companies as Targets Economic Upturn,” Reuters, July 21, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-xi/be-more-patriotic-chinasxi- tells-companies-as-targets-economic-upturn-idUSKCN24M1R3; and “China Unveils Outline for Strengthening Patriotic Education,” Xinhua Net, November 13, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019- 11/13/c_138549930.htm. Western travelers to China in the 19th and 20th centuries frequently commented on a lack of national morale in the Chinese military. For example, British Army officer Major Clarence D. Bruce, who commanded a Chinese regiment of volunteers in the British service during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, reflected on the presence of “a national military spirit” in China, ultimately concluding that “such a spirit at present exists or can be called into being in China by Chinese, I am unable to believe.” See: In the Footsteps of Marco Polo, 361-363.

6 Lee Smith, “Assabiya Wins Every Time,” Tablet, August 18, 2021, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/assabiya-lee-smith; and Amy Kazmin, Benjamin Parkin, Katrina Manson, “Low Morale, No Support and Bad Politics: Why the Afghan Army Folded,” Financial Times, August 15, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/b1d2b06d-f938-4443-ba56-242f18da22c3.

7 For deeper analysis of China’s perception of and relationship with its ethnic minority populations, see: Owen Lattimore, Inner Asian Frontiers of China, New York, NY: American Geographical Society, 1940, Chapters 1-3.

8 “Xi Jinping Gives Important Instructions on Anti-Drug Work,” Xinhua News Agency, June 25, 2018, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-06/25/content_5301084.htm. As part of its efforts to seek out drug users, for example, China has analyzed sewage for chemicals indicating drug consumption. See: David Cyranoski, “China Expands Surveillance of Sewage to Police Illegal Drug Use,” Nature, July 16, 2018, https://www. nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05728-3. China also employs capital punishment for a variety of drug-related crimes, including drug manufacturing and trafficking, and occasionally holds public trails for execution sentencing over drug crimes. See: “Briefing for Universal Periodic Review – China, The Death Penalty for Drug Offences,” Harm Reduction International, 2018, https://www.hri.global/files/2018/11/06/China_UPR_ briefing_-_Death_penalty_for_drugs_FI.PDF and Kerry Allen, “China Public Death Sentences Over Drugs Alarm Web Users,” BBC News, December 18, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-42403250.

9 “Drug Situation in China (2019),” Ministry of Public Security, June 28, 2020, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-06/28/content_5522443.htm.

10 Ibid; “Drug Situation in China (2020),” Ministry of Public Security, accessed via Guangdong Drug Rehabilitation Administration, July 19, 2021, http://gdjdj.gd.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/3/3349/post_3349119.html#3346.

11 For a historical example, see: Owen Lattimore, High Tartary, Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1930, 299. In this account, the governor of Sinkiang impedes collaboration between local leaders and residents by deliberately selecting “outlandish bumpkins” from the province Kan-su, who are “looked down on by other Chinese,” as leaders. The governor employs this strategy “because he knew they would not combine well with other Chinese in any intrigue against him.”

12 Marlène Laruelle and Sébestien Peyrouse, “Cross-border Minorities as Cultural and Economic Mediators between China and Central Asia,” The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Volume 7, No. 1 (2009): 111-113, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/105539/CEFQ200902.pdf.

13 Ibid, 112.

14 Several factors could potentially drive an increase in cross-border exchanges, including: 1) an influx into China of refugees fleeing the Taliban, as well as Taliban fighters seeking retribution for China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and 2) the exodus from China of Uyghurs, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, and other ethnic minorities fleeing persecution or seeking to join ethnic counterparts in Afghanistan with shared ideological interests. Shared interests could include support – although often exaggerated by Chinese leaders – by Uyghurs for the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement, which seeks Xinjiang’s establishment as an independent state and is active in Afghanistan, or Tajiks seeking to join counterparts in Afghanistan who supported the Taliban’s takeover in Badakhshan. See: Catherine Wong, “China Warns of Cross-Border Terror Leaks from Afghanistan,” South China Morning Post, September 9, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3148097/china-warns-cross-border-terror-leaks-afghanistan?; “Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on the Afghan Issue Among the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, September 8, 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/ t1905753.shtml; Tsukasa Hadano, “China Extends Hand to Taliban for Rebuilding with Eye on Xinjiang,” Nikkei Asia, August 27, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Afghanistan-turmoil/ China-extends-hand-to-Taliban-for-rebuilding-with-eye-on-Xinjiang; and Mumin Ahmadi, Mullorajab Yusifi, and Nigorai Fazliddin, “Exclusive: Taliban Puts Tajik Militants Partially In Charge of Afghanistan’s Northern Border,” Radio Free Europe, July 27, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/taliban-tajik-militants-border/31380071.html.

15 Baron tracking of reported terrorist attacks in Xinjiang occurring between 2012 and 2014.