Introduction

The nation’s capital has emerged in recent decades as a remarkably unrepresentative enclave. Although many major American cities have followed a similar course in the modern era, only one serves as the seat of a representative government for a continent-spanning nation. The profound economic and ideological asymmetry between Washingtonians and the “average American” increasingly defines and distorts political life. This trend undermines the capital city’s ability to accept democratic outcomes inconsistent with an intensifying monoculture and, ultimately, threatens the popular legitimacy of the federal government.

Prosperity on the Potomac

In 1950, the Washington, D.C. area ranked 10th in population among the nation’s metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), just behind St. Louis, Missouri.1 As people and capital have exited the nation’s heartland in subsequent decades, D.C.’s fortunes have far surpassed those of former peer cities. Since 1975, the first year on record for the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s House Price Index, housing values in the District have appreciated at a rate of almost two and a half times the national average, and at nearly three and a half times the rate of St. Louis. The Washington metropolitan area now stands at sixth in population at 6.4 million residents, while the St. Louis MSA has fallen to 21st at 2.8 million residents.2

Household income data reveal the Great Recession as an inflection point in the District’s economic rise. Through the early 2000s, household income in the District tracked the national median at a slight lag, reflecting the significant incidence of poverty in the city despite asset accumulation by the city’s well-to-do.3 The 2008 financial crisis marked the start of a sustained divergence, with the District’s income spiking that year above the flatlining national median.4 This gap would widen substantially. At its pre-pandemic peak, Washington, D.C.’s median household income reached $93,000, compared to $69,000 for the country overall.5 Northwest Washington, the area within the city that serves as home to many political elites, boasts a median household income of $159,000 and an average household income of $248,000.6

The Great Partisan Divide

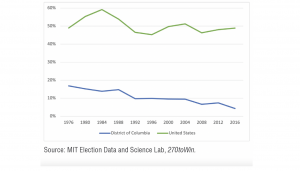

As in other high-density areas, the politics of the National Capital Region bear little resemblance to the roughly even partisan divide that characterizes national politics. Since the ratification of the 23rd Amendment granting the District the right to vote in presidential elections, the nation’s capital always has been heavily Democratic. Republicans nonetheless constituted a notable political minority. In recent presidential elections, however, the number of Republican voters in the District has dwindled to near trace-element levels, mirroring the trend in other “Super Zips.” During the four decades from 1976 to 2016, the share of votes cast in the District for non-Democratic presidential candidates plummeted by more than 75 percent, dropping into the low single digits.7 Even when accounting for the entire metropolitan area, a striking degree of political homogeneity has emerged. In the 2020 presidential election, the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area ranked the second-most Democratic on the entire East Coast, surpassed only by Pittsfield, Massachusetts.8

REPUBLICAN VOTE SHARE IN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, 1976-2016

The Monoculture Strikes Back

The election of Donald J. Trump in November 2016 offers a case study in the potential for the above-described asymmetry to exacerbate political instability. During the Obama Administration, federal civil servants generally embraced America’s political leadership, ideologically and culturally. “The stars are aligned,” declared Office of Personnel Management Director John Berry in 2009.9 By contrast, the Trump Administration was characterized from the start by internal resistance from the federal workforce.

Within two weeks of President Trump’s election, The Washington Post reported that “federal workers are in regular consultation with recently departed Obama-era political appointees about what they can do to push back against the new president’s initiatives.”10 Angered by President Trump’s unpredictability and disregard of bureaucratic norms, such opposition – termed by one academic “civil servant disobedience” – emerged across the seniority spectrum, from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) line officer refusals to execute deportation directives to an open no-confidence letter by a senior officer at the Department of Housing and Urban Development declaring his department’s political leadership untrustworthy.11 Among other measures signaling that the disdain was mutual, the Trump Administration recategorized policy-related civil servants under a new federal employee classification to strip them of protection from at-will firing.12 President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. rescinded this order upon his inauguration.13

“Washington’s socioeconomic and ideological homogeneity has rendered the city a deeply flawed venue for airing disputes between urban progressive and rural conservative voters.”

Any future Republican president this decade – even assuming strong leadership credentials and governing skills – almost certainly will prove fundamentally incompatible with the District as a community. A GOP commander-in-chief elected in 2024 or 2028 would have abundant incentives to attack the prosperity of the nation’s capital. Republican electoral strength depends heavily on rural voters. In 2020, President Trump won rural areas by 15 percent, compared to a 2 percent suburban deficit and a 22 percent loss among urban voters.14 For these reasons that transcend personality, even prospective Republican presidents with elite degrees and substantial records of public service – for example, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and Senators Tom Cotton (AR) and Josh Hawley (MO) – would be fortunate to face even modestly less hostile receptions than their GOP predecessor.

Implications

RED STATE ACTIVISM

Washington’s socioeconomic and ideological homogeneity has rendered the city a deeply flawed venue for airing disputes between urban progressive and rural conservative voters. Consequently, state officials in recent years have become the primary agents of political conflict. Corporate America now confronts a new reality in state houses across the country: when conservative counterrevolutionaries fail to receive a hearing from urban policy professionals in Washington, they look to states for action – and turn on even the most powerful corporations in their states that stand in their way.

THE END OF HOME RULE

Republican retaliation could include revoking the District’s self-governing municipal status under the District of Columbia Home Rule Act.15 Such an effort would not just represent a direct affront to proponents of D.C. statehood; it also would give Republicans, typically denied power over municipal questions in heavily Democratic cities, the opportunity to reject Democratic policies on law enforcement and public health. In her response to Congressman Andrew Clyde (R-GA-09)’s recent call to repeal the Home Rule Act, Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) captured the stakes of the conflict: “It’s something to be extremely concerned about, because the District may well find itself in the minority next term.”16 Should Republicans make good on these plans, debates over Washington’s own local governance may become proxy contests for the reassertion of political power in the nation more broadly by non-urban voters. In any such event, Republicans could unwittingly ignite protracted civil unrest in the seat of national government.

BREAKUP

Polling indicating that majorities and pluralities of Trump and Biden voters respectively express openness to secession has fueled speculation about a “national divorce.”17 More likely, red states will pursue targeted efforts to overcome Washington’s ideological hostility, developing a conservative equivalent to Democrats’ sanctuary state immigration policies. Conversely, Republicans might seek to break up Washington itself during their periods of control over federal levers of power. In 2018 and 2019, the Trump Administration announced plans to move several federal agencies out of Washington in a symbolic effort to make good on President Trump’s campaign pledge to “drain the swamp” and redistribute federal employment opportunities throughout the nation’s interior.18 The challenge of achieving long-term success in such efforts has already become clear: although two relocated Department of Agriculture research agencies will remain in Missouri, President Biden announced plans to return the Bureau of Land Management to Washington within days of his inauguration.19

Conclusion

America’s founders located the District of Columbia at some distance from New York, the nation’s financial center, to better reflect the variety characterizing the new, sprawling republic. In objecting to a motion to establish America’s capital at “the center of wealth, population, and extent of territory,” James Madison explained, “I move to strike out the word wealth, because I do not conceive this to be a consideration that ought to have much weight in determining the place where the seat of government ought to be. … Government is intended for the accommodation of the citizens at large.”20 Despite this hope, Washington, D.C. has diverged dramatically from the median of American economic and political life. The increasing wealth and near-total enlistment of the nation’s capital into a partisan mission risks creating a permanent state of conflict between the federal government and half the electorate. Such tension threatens to mire the U.S. public sector in debilitating dysfunction and create massive challenges for business leaders.

Endnotes

1 “1950 Census of Population: Preliminary Counts,” U.S. Department of Commerce, November 5, 1950, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1950/pc-03/ pc-3-03.pdf.

2 Baron analysis of 2020 Census estimates for Metropolitan Statistical Areas for April 1, 2020. “Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2021,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas. html#par_textimage_1139876276.

3 U.S. Census Bureau, Median Household Income in District of Columbia [MEHOINUSDCA646N] and Median Household Income in the United States [MEHOINUSA646N], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=P0Wq.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Numbers are for zip code 20016. “S1901 Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2020 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars),” U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, https://data. census.gov/cedsci/table?g=860XX00US20016&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S1901.

7 Baron analysis of “U.S. President 1976–2020,” MIT Election Data and Science Lab, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/42MVDX; and “Historical Timeline,” 270toWin, https://www.270towin.com/historical-presidential-elections/timeline.

8 Richard Florida, “How Metro Areas Voted in the 2020 Election,” Bloomberg, December 4, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-12-04/how-metro-areas-voted-in-the-2020-election.

9 John Berry, Remarks at the Human Capital Management Forum, November 17, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/documents/09-11-17_Remarks_at_ Human_Capital_Management_Forum_FINAL.pdf.

10 Juliet Eilperin, Lisa Rein, and Marc Fisher, “Resistance from Within: Federal Workers Push Back Against Trump,” The Washington Post, January 31, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/resistance-from-within-federal-workers-push-back-against-trump/2017/01/31/c65b110e-e7cb-11e6-b82f-687d6e6a3e7c_story.html.

11 Jennifer Nou, “Civil Servant Disobedience,” 94 Chicago-Kent Law Review 349 (2019), https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=4251&context=cklawreview.

12 Jim Eisenmann, “Trump’s Plan to Gut the Civil Service,” Lawfare, December 8, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/trumps-plan-gut-civil-service.

13 Executive Order No. 14003, 86 Fed. Reg. 7231, January 22, 2021, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/27/2021-01924/protecting-the-federal-workforce.

14 “Exit Polls,” CNN, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/election/2020/exit-polls/president/national-results.

15 Henry Rodgers, “House Oversight Republicans, Kevin McCarthy Plan November Surprise for D.C. Mayor Bowser,” Daily Caller, February 11, 2022, https://dailycaller. com/2022/02/11/house-oversight-republicans-kevin-mccarthy-mayor-muriel-bowser-washington-dc-crime-homelessness-mandates.

16 Press release, “Rep. Clyde: D.C.’s COVID Mandates Might be Gone, but Home Rule Repeal is Still Coming,” Office of Congressman Andrew Clyde, February 16, 2022, https://clyde.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=88; and Meagan Flynn, “Norton ‘Extremely Concerned’ About Possible Republican Bill to Repeal D.C.’s Home Rule,” The Washington Post, February 14, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/02/14/dc-home-rule-clyde-norton-repeal.

17 “New Initiative Explores Deep, Persistent Divides Between Biden and Trump Voters,” University of Virginia Center for Politics, September 30, 2021, https://centerforpolitics.org/ crystalball/articles/new-initiative-explores-deep-persistent-divides-between-biden-and-trump-voters.

18 Press release, “USDA to Realign ERS with Chief Economist, Relocate ERS & NIFA Outside D.C.,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 9, 2018, https://www.usda.gov/ media/press-releases/2019/06/13/secretary-perdue-announces-kansas-city-region-location-ers-and-nifa; and Stephanie Ebbs, “Is Trump Moving the Government Out of Washington? Five Things to Know,” ABC News, July 19, 2019, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-moving-government-washington-things/story?id=64428637.

19 Chuck Abbott, “Transplanted USDA Agencies Will Stay in Kansas City, Says Vilsack,” Food & Environment Reporting Network, April 26, 2021, https://thefern.org/ag_insider/ transplanted-usda-agencies-will-stay-in-kansas-city-says-vilsack; Executive Order No. 14003; and Eric Katz, “Interior Employees Impacted by Trump’s Relocations Rejoice as Biden Moves Agency Headquarters Back to D.C.,” Government Executive, September 20, 2021, https://www.govexec.com/management/2021/09/interior-employees-impacted-trumps-relocations-rejoice-biden-moves-agency-headquarters-back-dc/185456.

20 Speech of September 3, 1789, quoted in Jay Phillip Cost, One Great American System: Madison, Hamilton, and the Problem of Republican Nationalism, doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 2017, 68.

Image source: Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palmer_Alley_1.jpg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.