Introduction

America’s healthcare crisis primarily reflects plummeting population health, not a systemic failure in care. Conventional explanations of massive healthcare spending – technology, inefficiency, and corporate profits – overlook the underlying problem. Much-debated healthcare policy reforms mainly offer false hope. The health crisis reflected in exploding healthcare spending likely will compel a broader political response with the potential to reorder a sector that comprises nearly 18 percent of U.S. GDP. COVID-19 only has exacerbated an already dire situation and, combined with changes in political demography, increased the probability of extreme government intervention.

Rising Costs

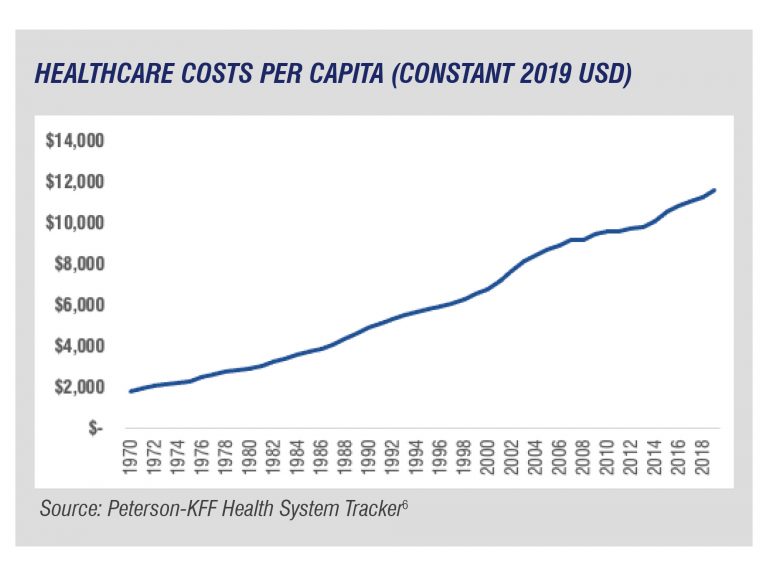

Healthcare expenditures have climbed dramatically in recent decades as measured in dollars, per capita, and as a percentage of GDP.1 In constant 2019 dollars, per capita healthcare spending has risen six-fold since 1970.2 In 2019, National Health Expenditures (NHE) were $3.8 trillion and represented 17.7 percent of GDP.3 Today, Medicare and Medicaid account for roughly a quarter of the federal budget.4 This trend shows no signs of abating; healthcare spending almost certainly will outpace GDP growth during the coming decade.5

The Traditional Diagnoses

Policy makers and opinion experts have offered three central explanations for rising costs:

Corporate Profits

Vice President Kamala Harris in a blog post during her presidential bid explained, “The bottom line is that healthcare just costs too much. … We will dramatically save money over the long run if we expand the Medicare program to include everyone and limit profits for drug companies and insurance companies.”7 On the Right, Senator Mike Braun (R-IN) opined, “Under the status quo, hospitals and insurers can charge astronomical prices without losing customers.”8 Despite such claims, healthcare profits do not account for the $3.8 trillion the United States spent in 2019 on healthcare expenditures. The Stern School of Business at New York University ranking of industries by net margins does not include any healthcare segment (pharmaceutical, insurance, or hospitals) among the top 10.9 In fact, “healthcare support services” (which includes insurance companies) earned some of the lowest gross margins compared to other industries, scoring in the bottom 10 of the 95 industries evaluated.10

Inefficiency

Dr. Atul Gawande, former CEO of Haven and a member of President Joe Biden’s pre-inauguration COVID-19 transition advisory board, argued in 2011 that rising medical costs result from a lack of coordination among different medical practitioners: “The public’s experience is that we have amazing clinicians and technologies but little consistent sense that they come together to provide an actual system of care, from start to finish, for people.”11 Medicare-for-All advocates highlight inefficiency as a key basis for enacting that policy proposal. Representative Pramila Jayapal (D-WA-7) opined in 2019 that Medicare-for-All “takes on costly waste and inefficiency in our current healthcare system.”12 According to the highest estimates, however, “failure of care coordination” accounts for two percent of NHE; including the highest estimates for “failure of care delivery” and “administrative complexity,” this number rises to 13 percent.13

Technology and pharmaceutical innovation

Neel U. Sukhatme and Maxwell Gregg Bloche of Georgetown University Law Center in 2019 claimed, “The main driving force behind rising spending, long term, is technological advance, fueled by health insurance’s promise of rich reward.”14 A briefing book from The Hastings Center, a think tank focused on bioethics, noted that “healthcare economists estimate that 40-50 percent of annual cost increases can be traced to new technologies or the intensified use of old ones.”15 A noteworthy body of research appears to contradict this assessment. For example, a 2018 study found that “spending on medical devices and in-vitro diagnostics totaled … 5.2 percent of total NHE.”16 Medical technology spending has averaged six percent of total NHE for the past 30 years.17 Study author and former U.S. Commerce Department economist Gerald Donahoe provided context: “In view of the conventional wisdom about the role of medical technology in driving up costs, it is surprising that the cost of medical devices has risen little as a share of total NHE.”18 Finally, a widely cited Milken Institute report, which examined “medical technology’s impact on the [U.S.] economic burden of disease,” found a net “positive benefit of more than $23 billion [per] year.”19

Medical drugs and pharmaceutical innovation also do not fully explain rising healthcare costs. Chris Pope of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research found that “out-of-pocket prescription drug spending accounts for 0.4 percent of U.S. households spending.”20 The dominant focus of policy makers on the above incremental factors obscures the genuine driver of healthcare expenditures: Americans increasingly require more medical care.

America’s Health Crisis

Life expectancy in the United States has stagnated since 2009 and currently ranks lowest among the G7.21 According to a recent study of 2016 data, “modifiable risk factors” accounted for nearly one quarter of healthcare expenditures in that year, or “$730.4 billion of total healthcare spending.”22 Furthermore, “researchers estimate that individual behavior determines the overall health and risk of premature death of an individual by 40 percent.”23

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explain at the top of their webpage on chronic diseases that “90 percent of the nation’s $3.8 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures are for people with chronic and mental health conditions.”24 Almost two-thirds of Americans suffer from a chronic disease, with four-in-10 experiencing two or more chronic diseases.25

Heart disease and stroke

Heart disease and stroke cost our healthcare system “$214 billion per year and cause $138 billion in lost productivity on the job.”26 Key risk factors for heart disease, the leading cause of death in the United States, are obesity, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use.27 Even among individuals with high genetic risk of coronary heart disease, “a favorable lifestyle was associated with a nearly 50 percent lower relative risk of coronary artery disease than was an unfavorable lifestyle.”28

Obesity

The Milken Institute found that “chronic diseases driven by the risk factor of obesity and overweight accounted for $480.7 billion in direct healthcare costs … with an additional $1.24 trillion in indirect costs due to lost economic productivity.”29 According to the CDC, “From 1999-2000 through 2017-2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity increased from 30.5 percent to 42.4 percent, and the prevalence of severe obesity increased from 4.7 percent to 9.2 percent.”30 Furthermore, 73.6 percent of adults aged 20 and over are overweight or obese.31 Finally, 81.6 percent of all adults “do not get the recommended amount of physical activity.”32

Lung cancer

More people in the United States die from lung cancer than any other type of cancer, with 80-to-90 percent of cases attributable to smoking.33 Smoking currently accounts for $170 billion in “direct medical care for adults.”34 While significant reductions in smoking have occurred – especially from the 1960s through the 1990s – “more than 16 million Americans are living [today] with a disease caused by smoking.”35 Today, tobacco use appears to be a significant form of self-medication: “Longitudinal data … indicates that smoking among adults without chronic conditions has declined significantly, but remains particularly high among those reporting anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders.”36

Addiction

The drug-related death rate rose nearly 4,000 percent from 1950 to 2017.37 Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found that “additional increases in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related liver mortality – particularly among those with a high school degree or less – are responsible for an overall increase in all-cause mortality among whites.”38 A recent McKinsey Global Institute study noted that “mortality [from substance abuse disorders] is six times higher in the United States than in Western Europe.”39 Similar to tobacco use, “self-medication with drugs or alcohol is commonly reported among adults with mood or anxiety disorders, and increases the risk of developing substance use disorders.”40

Mental illness

One in five U.S. adults experienced mental illness in 2019; more than 30 percent of U.S. adults report “symptoms consistent with an anxiety and/or depressive disorder.”41 The most acute rise has occurred among young people: between 2008 and 2017, “the amount of adults that experienced serious psychological distress” aged 18-25 rose 71 percent.42 Furthermore, among adolescents, “internalizing problems” – defined as anxiety, depression, suicidal thinking, and somatization disorders – rose “from 48.3 percent in 2005-2006 to 57.8 percent in 2017-2018, a 19.7 percent increase.”43 Spending on mental health treatment has increased from $172 billion (inflation adjusted) in 2009 to $225.1 billion in 2019, a roughly 30 percent increase.44 The chronic and other diseases afflicting so many Americans reflect an underlying health crisis, not systemic failures in healthcare financing or delivery.

Shifting Political Demography

The Republican Party has been transformed by a shift in support from suburban to rural voters. This change in the composition of the GOP’s electoral base has softened the party’s traditional opposition to government involvement in healthcare. Rural voters have become a central element of the Republican base. In 2008, rural voters favored the GOP by 16 percent, compared to roughly 36 percent in 2016 and 2020.45 In summary, today’s Republican Party represents voters with relatively greater healthcare needs and lower incomes, the combination of which has made public policy to subsidize expenditures and increase access substantially more attractive.

Rural America confronts serious health disparities relative to suburban populations. According to the CDC, “Rural residents often have limited access to healthy foods and fewer opportunities to be physically active compared to their urban counterparts, which can lead to conditions such as obesity and high blood pressure. Rural residents also have higher rates of smoking, which increases the risk of many chronic diseases.”46 Furthermore, Americans in rural areas more frequently die from preventable causes than Americans in suburban and urban areas.47

As such, the Right increasingly rejects laissez-faire economics and blames corporate America for rising healthcare costs. For example, conservative and populist journal American Affairs argued, “The U.S. system, whatever ‘market’ aspects it retains, has failed completely at containing costs compared to the rest of the world. There is, furthermore, no basis on which to believe that corporate health insurance bureaucracies ration care in a manner any more just or efficient than a government bureaucracy would.”48

Outlook

Corporations increasingly shoulder the blame for rising healthcare expenditures driven by a collapse in public health. As Medicare-for-All becomes the orthodoxy of the Democratic Party, Republicans have a powerful electoral interest in supporting greater government involvement in healthcare to help rural America. Although the confluence of these forces promises to produce a powerful anti-corporate response from the political system, America’s health crisis reflects problems much deeper than public policy.

Map (image): Drug Overdose Mortality by State, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

© 2021 Baron Public Affairs, LLC. All Rights Reserved. No part of these materials may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopy, recording or any other information storage or retrieval system known now or in the future, without the express written permission of Baron Public Affairs, LLC. The brief does not constitute advice on any particular investment or commercial issue or matter. No part of this brief constitutes investment or legal advice and is not to be relied upon as such. The unauthorized reproduction or distribution of this copyrighted work is illegal and may result in civil or criminal penalties under the U.S. Copyright Act and applicable copyright law.

Endnotes

1 Ryan Nunn, Jana Parsons, and Jay Shambaugh, “A dozen facts about the economics of the U.S. health-care system,” The Brookings Institution, March 10, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-dozen-facts-about-the-economics-of-the-u-s-health-care-system.

2 Rabah Kamal, Daniel McDermott, Giorlando Ramirez, and Cynthia Cox, “How has U.S. spending on healthcare changed over time?,” Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, December 23, 2020, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-spending-healthcare-changed-time/#item-usspendingovertime_3.

3 “NHE Fact Sheet,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.

4 “The Federal Budget in 2019,” Congressional Budget Office, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-04/56324-CBO-2019-budget-infographic.pdf.

5 “Healthcare Costs For Americans Projected To Grow At An Alarmingly High Rate,” Peter G. Peterson Foundation, May 1, 2019, https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2019/05/healthcare-costs-for-americans-projected-to-grow-at-an-alarmingly-high-rate.

6 Kamal, McDermott, Ramirez, and Cox, ibid.

7 Kamala Harris, “My Plan For Medicare For All,” Medium, July 29, 2019, https://kamalaharris.medium.com/my-plan-for-medicare-for-all-7730370dd421.

8 Senator Mike Braun, “It’s time to reveal true cost of healthcare prices,” Fox Business, June 30, 2020, https://www.foxbusiness.com/money/reveal-real-health-care-prices-sen-mike-braun.

9 Aswath Damodaran, “Margins by Sector (U.S.),” Stern School of Business at New York University, January 2021, http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/margin.html.

10 Ibid.

11 Atul Gawande, “Cowboys and Pit Crews,” The New Yorker, May 26, 2011, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/cowboys-and-pit-crews.

12 Representative Pramila Jayapal, “Medicare for All offers comprehensive solution for our broken system,” Modern Healthcare, September 21, 2019, https://www.modernhealthcare.com/opinion-editorial/medicare-all-offers-comprehensive-solution-our-broken-system.

13 William H. Shrank, Teresa L. Rogstad, and Natasha Parekh, “Waste in the U.S. Health Care System Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings,” JAMA, (2019): 1501-1509, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2752664.

14 Neel U. Sukhatme and Maxwell Gregg Bloche, “Health Care Costs and the Arc of Innovation,” Georgetown University Law Center, 2019, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3171&context=facpub.

15 Daniel Callahan, “Health care costs and medical technology,” in From Birth to Death and Bench to Clinic: The Hastings Center Bioethics Briefing Book for Journalists, Policymakers, and Campaigns, ed. Mary Crowley, Garrison, NY: The Hastings Center, 2008, 79-82, https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Health-Care-Costs-BB17.pdf.

16 Gerald Donahoe, “Estimates of Medical Device Spending in the United States,” Advanced Medical Technology Association, November 2018, https://www.advamed.org/sites/default/files/resource/estimates_of_medical_device_spending_in_the_united_states_november_2018.pdf.

17 “The Value of Medical Technology,” Advanced Medical Technology Association, 2013, https://www.advamed.org/sites/default/files/resource/995_092915_value_king_avalere_reports_infographic_final.pdf.

18 Donahoe, ibid.

19 Press release, “Medical Technology: Benefits Far Outweigh Costs Milken Institute report sizes up overall economic impact of ‘med tech’,” Milken Institute, April 8, 2019, https://milkeninstitute.org/articles/medical-technology-benefits-far-outweigh-costs-milken-institute-report-sizes-overall.

20 Chris Pope, “Issues 2020: Drug Spending Is Reducing Health-Care Costs,” Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, November 6, 2019, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/issues-2020-drug-prices-account-for-minimal-healthcare-spending#notes.

21 “Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2017,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2018/004.pdf; and “Life expectancy at birth,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019, https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/life-expectancy-at-birth.htm.

22 Howard J Bolnick, Anthony L Bui, Anne Bulchis, Carina Chen, Abigail Chapin, Liya Lomsadze, et al, “Health-care spending attributable to modifiable risk factors in the USA: an economic attribution analysis,” The Lancet, Vol. 5, Issue 10, (October 2020), https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30203-6/fulltext.

23 Alison Rodriguez, “Addressing Social Determinant Factors That Negatively Impact an Individual’s Health,” American Journal of Managed Care, August 20, 2017, https://www.ajmc.com/view/social-determinant-factors-can-negatively-impact-an-individuals-health.

24 “Health and Economic Costs of Chronic Diseases,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 12, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm.

25 “Chronic Diseases in America,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 12, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm.

26 “Health and Economic Costs of Chronic Diseases,” ibid.

27 “Heart Disease Facts,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 8, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm.

28 Amit Khera, Connor Emdin, Isabel Drake, et al, “Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Coronary Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine, (2016): 2349-2358, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27959714.

29 Hugh Waters and Marlon Graf, “The Cost of Chronic Diseases in the U.S.,” Milken Institute, May 2018, https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/Mi-Americas-Obesity-Crisis-WEB.pdf.

30 Craig Hales, Margaret Carroll, Cheryl Fryar, and Cynthia Ogden, “Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db360-h.pdf.

31 “Obesity and Overweight,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 11, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm.

32 “Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity,” Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020, https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Nutrition-Physical-Activity-and-Obesity.

33 “Tobacco Use and Lung Cancer,” National Cancer Institute, https://gis.cancer.gov/mapstory/tobacco/index.html; and “Lung Cancer Statistics,” National Cancer Institute, September 22, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/statistics/index.htm.

34 “Smoking and Tobacco Use: Fast Facts,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 21, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm.

35 Ibid.

36 “Do people with mental illness and substance use disorders use tobacco more often?,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, January 2020, https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco-nicotine-e-cigarettes/do-people-mental-illness-substance-use-disorders-use-tobacco-more-often.

37 “Long-Term Trends in Deaths of Despair,” U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, September 5, 2019, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/9/long-term-trends-in-deaths-of-despair.

38 Anne Case and Angus Deaton, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” The Brookings Institution, August 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/casetextsp17bpea.pdf.

39 “Prioritizing health,” McKinsey Global Institute, July 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/Prioritizing%20health%20A%20prescription%20for%20prosperity/MGI_Prioritizing%20Health_Report_July%202020.pdf.

40 Aaron Sarvet, Melanie Wall, Katherine Keyes, Mark Olfson, Magdalena Cerdá, and Deborah Hasina, “Self-medication of mood and anxiety disorders with marijuana: Higher in states with medical marijuana laws,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 186, (2018): 10-15, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5911228.

41 “Mental Health By the Numbers,” National Alliance on Mental Illness, December 2020, https://www.nami.org/mhstats; and “Mental Health and Substance Use State Fact Sheets,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 19, 2020, https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheet.

42 Jaime Rosenberg, “Mental Health Issues On the Rise Among Adolescents, Young Adults,” American Journal of Managed Care, March 19, 2019, https://www.ajmc.com/view/mental-health-issues-on-the-rise-among-adolescents-young-adults.

43 “Survey Data Confirm Increases in Anxiety, Depression and Suicidal Thinking Among U.S. Adolescents,” Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, March 25, 2020, https://www.jhsph.edu/news/news-releases/2020/survey-data-confirm-increases-in-anxiety-depression-and-suicidal-thinking-among-u-s-adolescents.html.

44 “The U.S. Mental Health Market: $225.1 Billion In Spending In 2019: An OPEN MINDS Market Intelligence Report,” Open Minds, May 6, 2020, https://openminds.com/intelligence-report/the-u-s-mental-health-market-225-1-billion-in-spending-in-2019-an-open-minds-market-intelligence-report; and “Projections of National Expenditures for Treatment of Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2010-2020,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4883.pdf.

45 Alexandra Kanik and Patrick Scott, “The urban-rural divide only deepened in the 2020 U.S. election,” City Monitor, November 11, 2020, https://citymonitor.ai/government/the-urban-rural-divide-only-deepened-in-the-2020-us-election.

46 “Rural Health,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, July 1, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/rural-health.htm.

47 Macarena C. Garcia, Lauren M. Rossen, Brigham Bastian, et al, “Potentially Excess Deaths from the Five Leading Causes of Death in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties – United States, 2010-2017,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 8, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/ss/ss6810a1.htm; and “Rural Americans are dying more frequently from preventable causes than their urban counterparts,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 7, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p1107rural-americans.html.

48 The Editors, “Our Policy Agenda,” American Affairs, Summer 2017, https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/05/our-policy-agenda.